Source: joycewallace1@blogspot.com

He was nervous, excited and scared, dreading where they’d send him.

It wasn’t that he was a coward, but he had his reasons.

His uniform was starched and crisp and clean, except for the dust that stirred around the cuffs and over the insteps of his glossy black shoes.

There was a single light on in the house, and the faint sound of a gospel choir building carried on the cool early morning air. Through the window he could see a woman was at the stove, and she hummed along in time with the gospel choir, a good voice, steady and clear. With the sound of the choir came the smell of bacon and coffee, faint at that distance, but there.

A slender brown hand with a spatula deftly flipped a flapjack in the air. Putting the flapjacks in the oven to keep warm while the bacon browned, she poured herself some coffee from the percolator and disappeared from view.

From what he could see, no one else seemed to be up, or perhaps no one else was there; she’d kept to herself since her husband died not too long ago.

The door opened, then the screen door squeaked, and the woman stepped out onto the porch into the coolness, and took a deep breath, running her free hand through her hair, the steam from the coffee cup rising like morning vespers. She still had her robe on. It was old and worn, like a well used Bible, and almost as sacred.

Sipping coffee, she looked down the road awhile at first, and Willie said, “Good morning, Darlene.”

She jumped and gave a little cry, turned, and smiled at him.

“Good morning, Willie. Didn’t see you there! Where you goin?”

Then she saw the uniform, tinged with blue in the predawn light.

“Oh,” was all she said. She felt flashes of anger and sadness, but managed, somehow, to keep from saying more.

Willie’s green cap was in his hand, and he was twisting it.

“Sorry ‘bout that, Darlene, didn’t mean to startle you.”

“Come on over here and get yourself something to eat; the bus ain’t due yet.”

“Don’t wanna be no trouble.”

She smiled. “I didn’t ask you to be no trouble, I told you to come get something to eat.”

“You sure?”

She put her hands on her hips.

“Willie, my bacon’s almost done. When this door is closed, it’s closed.”

Willie came over, the fine dust on the road made little coronas around his feet, as if he were a prophet traversing the dunes.

Darlene went in ahead of him.

“Go on and sit down,” she told him.

Willie sat and scooted his chair up to the table as she put a steaming plate in front of him, took out some syrup and butter, and poured his coffee and added a small glass of apple cider.

Then she served herself; he got up to hold her chair, and sat back down.

Holding hands across the table, together they said grace.

*****************

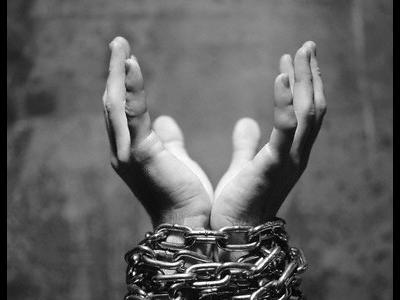

“Don’t see why I got to go,” he said. “They treat us like dirt here, and want us to go help somebody else from being treated like dirt. Don’t make no sense.”

Darlene sat back and sighed. “No, it don’t.”

The somber click and scrape of utensils filled the heavy silence for a time.

“They even separate us there; don’t want us next to them on the way over, and don’t care if we…”

He wasn’t looking at her. It seemed like he wanted to cry but didn’t dare. Seemed like he wanted to bolt and run down the road and never look back, but he couldn’t.

“Willie.”

Something in the way she said his name got his attention. She took his hand.

“It don’t matter what they do, you got to come back alive, whatever it takes. Don’t you let them break you, hear? You got to come back sane and whole. You got that baby coming, and it’s depending on daddy, right now, to come back.”

**********

Darlene’s father was nervous that morning, his hands fidgeting with his hat, and her mother kept adjusting things on him, putting off his leaving as long as possible, as he stood there and let her put it off.

Her hands were busy adjusting from the inside out until there was nothing more: his tie his shirt collar, his jacket collar, the cuffs of his sleeves, the hem of his pants, hands brushing, tugging, tucking, when all she wanted to do was grab him and never let him go to that meeting about the coming protests.

Out of things to do, she looked at her husband, tears in her eyes, untouched by either of them, until he reached out and pulled her close, and looked down at the upturned faces of his little girls, not comprehending, but feeling the anxious charge in the air between their parents, his own eyes filling, his wife’s tears wetting his jacket, her lips by his ear.

“ I don’t care ‘bout what you got to do out there, David, to make things better for everybody else, you just make sure you come home. These girls need their daddy, and I need my husband, and I know you scared, but you got to come back, and that’s all there is to it.

"You hear me, David?”

**********

“You hear me, Willie?”

Willie nodded and got his breathing back under control.

They finished breakfast in silence, though neither of them felt much like eating now; it was just sin to waste food.

Darlene cleared the table, and Willie stood up; he held the door for her as they went outside, and saw the puff of dust down the road from the bus tires.

“Guess it’s time.”

“Let’s pray.” She took his hand again.

They prayed for protection, his safe return, strength for Clara, and health for his new baby, in Jesus’ Name, amen.

The bus hissed to a stop.

“You comin, boy?”

“Yessir.”

"Say goodbye, then."

Willie and Darlene embraced.

“I’m scared, Darlene.”

“ I know,” she said against his ear, “I know that, Willie. And so is Clara, and so is your baby. You’ll probably be scared every day you spend over there.”

Stepping out of his arms, her eyes searched his.

“But you got to come back,” her eyes welled up, “and that’s all there is to it.”

He swallowed, nodded, wiped his own tears away with his mangled green cap.

“Thank you for breakfast,” he said, though it wasn’t all he meant.

A horn shattered the morning quiet.

“Ain’t got all day, boy!”

“Comin’, sir!”

“ Weren’t no ‘trouble’.”She let her tears fall, and smiled through them, and Willie walked down the steps, over the road, into the bus. Finding an empty seat by the window, he looked out at her, and she kept the smile she didn’t feel on her face, and waved as the bus took him to his destiny.

And as the birds began to sing, all that remained of Willie were his footprints leading to and from her door, and the dust from the tires settling back down, and the paling light of the morning sun breaking over the horizon, as Darlene wiped her eyes on the sleeve of her robe, and went back inside, humming low with the radio choir.

©Alfred W. Smith, Jr.

April 21st, 2014

All rights reserved

comments prior to edit