Source: deviant art.com

The fire could never go out, and the wood could never run low, and the coal had to be fetched in between, otherwise, the drifts and depths of the snow would prevent them from going to the barn.

Jorie hated putting on the snowshoes, but she brought back what her size would allow her to carry.

She was slender, but strong, and the constant motion through the snow built up her legs.

Her mother had to walk long distances to find the sheltered herbs they used, and her father had to hike the mountains when they ran out of game.

The white, shaggy goats were difficult to hunt, and treacherous, and more than one man in her village had tumbled down the icy slopes into the waiting ravines, with their frozen rivers and sharp rocks, and high branches.

Sometimes, you could see some of their bones lying where they fell; scavengers ripped and carried off the best parts while they still had flesh.

Jorie would shudder, and move closer to her father, who’d give her a reassuring smile, and hold her hand until she let go.

He taught her to hunt; he tried to teach her mother too, and though she had no problem with skinning and butchering and cooking, the actual taking of the life she prepared for their meals was not something she could bring herself to do.

They could have no other children, so her father taught her what he would’ve taught his son.

The elders didn’t like it, but there had never been a set rule against it; no one but her father had ever done it, but as none of the other fathers with no sons seemed inclined to do the same, they turned a blind eye to it.

He knew they looked at him askance, and talked when he wasn’t there, but he was not of a mind to leave his family unable to fend for themselves in this harsh landscape, should he wind up in the ravine one day.

She’d took to hunting quickly, mostly because she didn’t want to be out in the cold at first, but later, as she grew and learned how to settle down, and get acclimated to become part of her surroundings, she realized that in such a frosty climate the wind could change on a dime, alerting the restless herd to the hunter, and the prey would disappear in a flash of fur, hooves and horns.

The goats being difficult to hunt, the kill had to be on the first shot; the long winters were not forgiving to the unskilled. Jorie and her father sometimes found those bones too, buried under deep drifts, their weapons next to them.

Jorie loved her homeland, though it was grueling, but as she got older, she found herself growing restless, and her father growing inexplicably overprotective. Her mother seemed to look at her differently too, and one day, over a cup of herb tea, she explained.

“You’re becoming a woman, Jorie."

And when all Jorie gave was a blank stare, her mother told her what she needed to know.

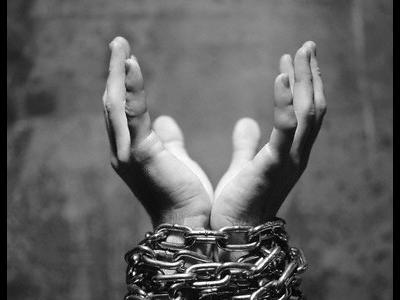

“And you must keep the boys at bay; don’t let them touch you. These hills are isolated, and many a young girl’s prospects have been ruined by young men with wild urges they’re encouraged, even expected, to indulge.”

Jorie knew of such a girl: her friend Sereda was swollen with child now, and she’d been set to marry another boy from a wealthier place. Jorie was visiting when the boy’s father came to demand back the bride price, and she remembered the shame on the face of Sereda and her father.

The man had cursed her as he left, vowing to return, and Sereda’s father fought him, but he managed to scramble out from under him, and ran, wiping his bleeding mouth on his sleeve, spitting blood through the holes where some of his teeth had been, cursing the while.

Jorie had held Sereda while she cried, and there was nothing else to be done for it.

Sereda was due any day now, and what her parents would do with an extra mouth to feed was beyond them all.

Jorie overheard her own father say, If he’s smart, he’ll drop it in a snowbank.

Her mother was horrified at the suggestion, but Jorie herself had mixed feelings: it would solve Sereda’s problem, but it wouldn’t repair her reputation.

The injustice of it was, the boy had forced himself on Sereda, or so she told Jorie, who didn’t know whether or not to believe her, since she’d seen the way Sereda side-eyed the strongest boys in the village.

Such mysteries were not for her.

Not yet.

Maybe not ever.

The epiphany came to her like the song of a muse:

I have to go.

**************

“Come with me, Sereda.”

“Look at me, Jorie. Do you honestly think I’d survive?”

“You will if you’re with me; I know these mountains. I know where the dangers are.”

“And you’ve never been beyond them, at least not without your father. You’ll die, Jorie, sure as my baby will be born, you will die.”

Jorie hugged her.

“This is farewell, then.”

Sereda returned the embrace, and Jorie felt a tear on her friend’s cheek.

She wiped it, and kissed the cheek, and let her friend go.

***************

Pretending all was well, she went to bed, but didn’t go to sleep.

The moon rose full and pale, tinting the snow to silver and the tree shadows to a deep shade of blue.

Jorie had kissed her parents good-night, and they all said their prayers together, the normal family ritual.

When the moon was near its zenith she got up, and took out the sack she packed with supplies that afternoon after telling her parents she would nap.

Slipping out the door, dressed lighter than she should have been for the colder night, but not wanting to be weighed down in the mountain passes, she put on the hated snowshoes, and began walking, the high moon lengthening her shadow behind her, her strong legs pistoning, taking her up the first incline of the foot of the mountain, her breath misting like dreams before her, and the stars twinkling in amusement at the foolish girl walking in the deep, silvery snow so far below.

© Alfred W. Smith Jr. 2015

comments prior to edit